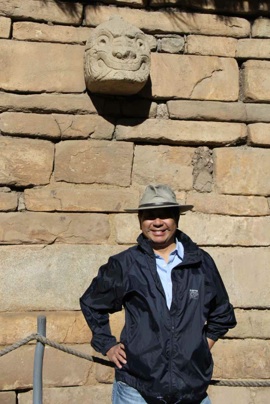

In July 2012, Peace Media went to Peru to investigate the link between the ancient Incan civilization and ancient Chinese civilization, including: Chavín de Huántar, Sechin, Huaca de la Luna and Trujillo etc. as well as visited several related museums.

Sunny Kuo (right 1) with Mario Osorio (right 2) and his team

Chavín de Huántar

http://baike.baidu.com/view/123615.htm

Chavín de Huántar is an archaeological site containing ruins and artifacts constructed beginning at least by 1200 BCE and occupied by later cultures until around 400-500 BCE by the Chavín, a major pre-Inca culture.

Chavín de Huántar has been designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

This archeological site is a large ceremonial center that has revealed a great deal about the Chavín culture. Chavín de Huántar served as a gathering place for people of the region to come together and worship. The transformation of the center into a valley-dominating monument had a complex effect; it became a pan-regional place of importance. People went to Chavin de Huantar as a center: to attend and participate in rituals, consult an oracle, or enter a cult.

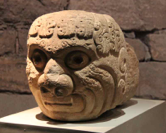

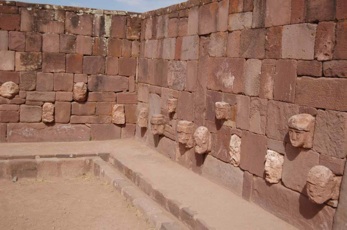

There are three important artifacts which are the major examples of Chavín art. These artifacts are the Tello Obelisk, Tenon Heads, and the Lanzón.

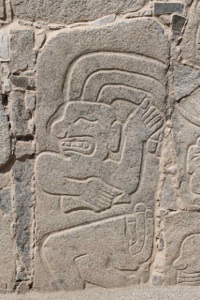

The role of hallucinogenic snuffs in shamanistic transformation is clearly expressed in the tenoned heads which gazed outwards from the parament of the Old Temple. They represent different stages in the drug-induced metamorphosis of the religious leaders (or their mythical prototypes) into their jaguar or crested-eagle alter egos. One set of these sculptures represents naturalistic anthropomorphic faces with almond-shaped eyes, bulbous noses, and closed mouths; their most distinctive features are an unusual hair arrangement - often a sort of top knot - and a wrinkled face, as if they were experiencing the onset of nausea. A second group of tenoned heads portray strongly contorted anthropomorphic faces, gaping round eyes, and mucus dripping from their nostrils, either slightly or in long flowing streams; the features and hairstyle suggest that the same group of individuals is being shown. The depiction of nasal discharges in prominent public contexts is alien to Western religious traditions, but its significance becomes clear from accounts of hallucinogenic snuff use among lowland South American Indians.

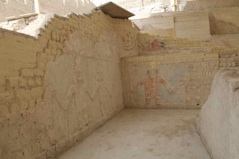

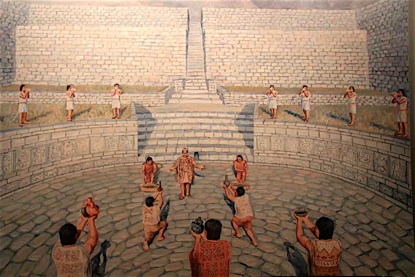

Chavin Temple

The Chavin temple grew through time as pilgrims brought wealth to the site. To the Old Temple (right), was added the New Temple, built at the height of the site's power (ca. 400- 200BCE)

Near and within the the Old Temple complex are a series of galleries, including the Gallery of the Offerings, the Gallery of the Bats, and the Gallery of the Labyrinths. The Lanzón is located centrally. The famous Black and White Portal fronts the New Temple, while the Old Temple is fronted by a sunken circular courtyard in its plaza.

Lanzón

The Lanzón, deep inside the New Temple of Chavin, stands on the central axis of the Old Temple and at the crossroads in a labyrinth of tunnels. The shaft above its head has earned it the name of "Big Lance," from its resemblance to a blade thrust into the earth.

This Lanzón, which is made of granite, stands 15 feet tall and contains the principal deity sculpted on each side. Upon flattening the Lanzón, one can clearly see the principal deity’s fierce eyes and fangs. One of the principal deity’s hands is raised up, while the other is lowered. Its stance indicates that it is the central axis between the heaven, earth and underworld.

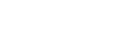

Raimondi Stela

This detail of the Raimondi Stela shows Chavín stone sculpture at its finest. The polished, flat surface, crisply carved lines, and deep spaces were made in hard granite without metal tools. Known as the Staff God, this is a variant of the principal Chavín deity. Its headdress turns into a monster head when inverted.

Such visual effects are hallmarks of Chavín style, as is the bilateral symmetry.

Tello Obelisk

One of the most spectacular sculptures at Chavín is the Tello Obelisk, which depicts an anthropomorphic cayman as the progenitor of useful plants and animals. At the notch near its top is a stepped cross with a circle in its center, a motif symbolizing the unity of the cosmos. Widespread in the Pre-Columbian Andes, the motif is found in Andean art to this day.

Seven Star Stone Slab

On the southwest corner of the main square, archaeologists discovered a 10 ton limestone plate slab with seven round pits on top. North American archaeologist Gary Urton believes that the seven small pit arrangement coincides with the Taurus constellation. Scholars have speculated that the Chavín de Huantar main square may have held prayer activities, including astronomical phenomena related to agricultural production.

In 1970 Director of the Institute of Archaeology, Xia Nai investigated the Chavín de Huantar ruins in Peru, and engaged in exchanges with Peruvian archaeologist Columbus Gonzalez

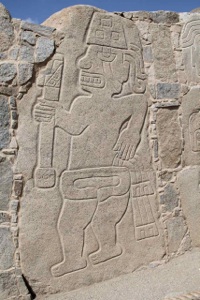

Cerro Sechín is an archaeological site in Casma Province of northern Peru. Dating back to 1600 BC, the site was discovered by Peruvian archaeologists Julio C. Tello and Toribio Mejía Xesspe on July 1, 1937. Tello believed it was the capital of an entire culture, now known as the Sechín Culture. Notable features include megalithic architecture with carved figures in bas-relief, which graphically depict human sacrifices. Cerro Sechín is situated within the Sechin Complex, as are Sechin Alto, Sechin Bajo, and Taukachi-Konkan. The slabs at Cerro Sechin may represent the central Andes' oldest known monumental sculpture.

Chan Chan Ruins

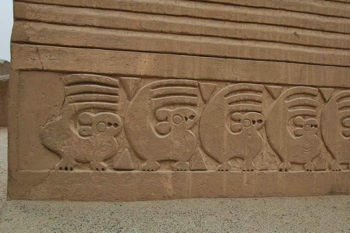

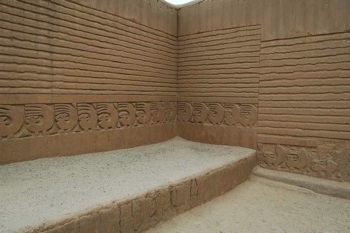

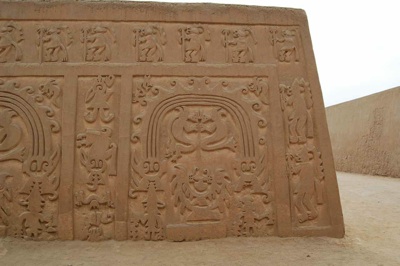

The largest Pre-Columbian city in South America, Chan Chan is an archaeological site five kilometers west of Trujillo, Peru. Chan Chan was constructed by the Chimor (the kingdom of the Chimú), a late intermediate period civilization which grew out of the remnants of the Moche civilization. The adobe city of Chan Chan, the largest in the world, was built around 850 AD and lasted until its conquest by the Inca Empire in 1470 AD. The city has ten walled citadels which housed ceremonial rooms, burial chambers, temples, reservoirs and residences. It was the imperial capital where 30,000 people lived.

Friezes featuring repetitious images of these curious squirrel-like animals—possibly nutria or coypu—adorn long stretches of the walls of Chan Chan. The enormous site has been identified as the ancient city of Chimor, capital of the Chimor (now known as Chimu) kingdom.

The so-called Temple of the Rainbow at Chan Chan is decorated, like many of the sprawling city’s structures, with striking adobe reliefs displaying animal and geometric motifs. The design of this panel is particularly complex.

Huaca de La Luna

Huaca de la Luna ("Temple/Shrine of the Moon") is a large adobe brick structure built mainly by the Moche people of northern Peru. Huaca de la Luna served a largely ceremonial and religious function, though it contains burials as well.

The Huaca de la Luna itself is a large complex of three main platforms, each one serving a different function. The northernmost platform, at one time brightly decorated with a variety of murals and reliefs, was destroyed by looters. Because of this, the central and southern platforms have been the focus of most excavations. The central platform has yielded multiple high-status burials interred with a variety of fine ceramics, suggesting that it was used as a burial ground for the Moche religious elite, while the Huaca del Sol may have been used for the interment of rulers.

Huaca de La Luna was decorated in registers of murals which were painted in black, bright red, sky blue, white, and yellow of spiders, fish and two headed snakes, as well as prisoners of war, farming and so on.

Many of these depict a deity now known as Ayapec. "Ayapec" is a pre-Quechua word translating as all knowing.

Huaca Cao Viejo

Huaca Cao Viejo (or Huaca Blanca) was built by the Moche sometime between 1 and 600 AD. Huaca Cao Viejo is famous for its polychrome reliefs and mural paintings, and the discovery of the Señora de Cao, the first known Governess in Peru.

Museo Tumbas Reales de Sipan

http://baike.baidu.com/view/327185.htm

The museum's main attraction is the Lord of Sipan and his entourage, who accompanied him to the afterworld with him. The warriors who were buried with him had amputated feet, as if to prevent their leaving the tomb. The women were dressed in ceremonial clothes. Dogs, llamas, and more than 80 huacos (works of ceramic pottery) were also buried in the tomb.

The clothing of this warrior and ruler suggest he was approximately 1.67 m tall. His jewelry and ornaments indicate he was of the highest rank, and include pectoral, necklaces, nose rings, ear rings, helmets, falconry and bracelets. Most were made of gold, silver, copper and semi-precious stones. In his tomb, more than 400 jewels were found.

Because of his high rank, the ruler was buried with six people, three women (possibly his wife & concubines but they had died some time prior to him), two males (probably warriors) and a child.

Sumptuous golden Lambayeque keros such as these were used in drinking rituals. The repeating pattern of the Sican Lord on one vessel and the turquoise inlays on the others exemplify the preference for luxury items that display a relatively low level of symbolism but are fashioned from materials of great value.

Machu Picchu

http://baike.baidu.com/view/62204.htm

Machu Picchu, which means “Old Mountain” in Quechua, is a 15th century Incan site located 2,430 above sea level. Most archaeologists believe that Machu Picchu was built as an estate for the Inca emperor Pachacuti (1438-1472).

Machu Picchu was built in the classical Inca style, with polished dry-stone walls. Its three primary structures are the Intihuatana (Hitching post of the Sun), the Temple of the Sun, and the Room of the Three Windows.

The Intihuatana stone is one of many ritual stones in South America. These stones are arranged to point directly at the sun during the winter solstice. The name of the stone is derived from the Quechua language: inti means "sun", and wata- is the verb root "to tie, hitch (up)" (huata- is simply a Spanish spelling). The Quechua -na suffix derives nouns for tools or places. Hence inti watana is literally an instrument or place to "tie up the sun", often expressed in English as "The Hitching Post of the Sun". The Inca believed the stone held the sun in its place along its annual path in the sky.

Tiwanaku Ruins

http://baike.baidu.com/view/85776.htm

Tiwanaku is an important Pre-Columbian archaeological site in western Bolivia, South America. Tiwanaku is recognized by Andean scholars as one of the most important precursors to the Inca Empire, flourishing as the ritual and administrative capital of a major state power for approximately five hundred years. The area around Tiwanaku may have been inhabited as early as 1500 BC as a small agriculturally based village.

Gate of the Sun

http://baike.baidu.com/view/46063.htm

One of the most impressive artistic and symbolic Andean patterns is the Sun Gate at Tiwanaku. It's thick stone slab, weighing several tons, has an entrace door carved with patterns of a god, which is accompanied by smaller winged "angels". This "god" is reminicent of the early staff god found on the Chavin de Huantar Raimondi stele, or the supreme Inca god Virachocha.

The view from a sunken plaza of the reconstructed portal of the Kalasasaya at Tiwanaku. The projecting tenon heads are reminiscent of the NewTemple sculptures at Chavin de Huantar, although these Tiwanaku heads show no signs of the effects of hallucinogens and their symbolism is uncertain.

Ceremonies at the Circular Plaza were not only accompanied by the pututo’s chant but also the jaguar’s roar reproduced through an acoustic canal located under the Lanzón.

Pututo Shell

Lanzón

Tenon Head

(First Stage)

Tenon Head

(Second Stage)

Tenon Head

(Third Stage)

Tenon Head

(Fourth Stage)

La Dama de Cao Museum

Burial site of La Dama de Cao

Lord of Sipan burial site

Lord of Sipan burial site

Chavin de Huantar Tenon Heads

Lanzón Diagram